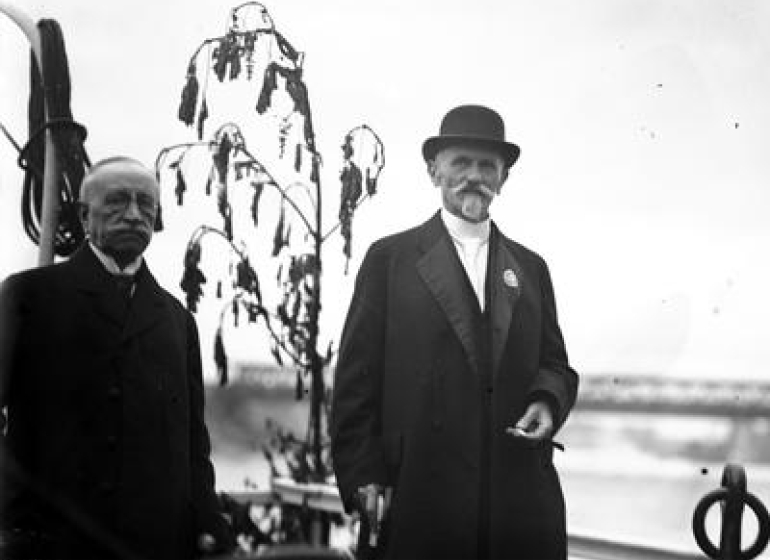

Stanisław Wojciechowski (1869–1953)

A revolver made a rather early appearance in the life of Stanisław Wojciechowski, in his memories — in his early youth. He was a student of the University of Warsaw, or, more precisely, of the Russian Imperial University in Warsaw. Besides his own university studies, he was also involved with workers’ self-education. He rented a room at Książęca Street, with an independent entrance from the staircase. One day, in 1891, he fell victim to a thief, who stole from him a suitcase full of underwear. Nothing strange there — both a suitcase and underwear represented quite some value in those times and were easy to sell on the street or in a bazaar. Not many goods were produced back then, but their quality was good, so they served their owners for many years. The problem was that a hectograph and a revolver were also found in that suitcase. The stashing in of a hectograph, which is a simple copying device, could be understandable because self-education necessarily had to involve some publishing activity outside of the reach of tsarist censorship. But a revolver? All the more so considering that Wojciechowski had never said anything about any armed resistance before. The young student made his decision immediately. At once, he fled his residence and into Hortensji Street, where he found a safe room on the fifth floor of one of the townhouses — ‘safe’ because all other rooms were inhabited by students alike to himself and the servants could be trusted (or so the students thought).

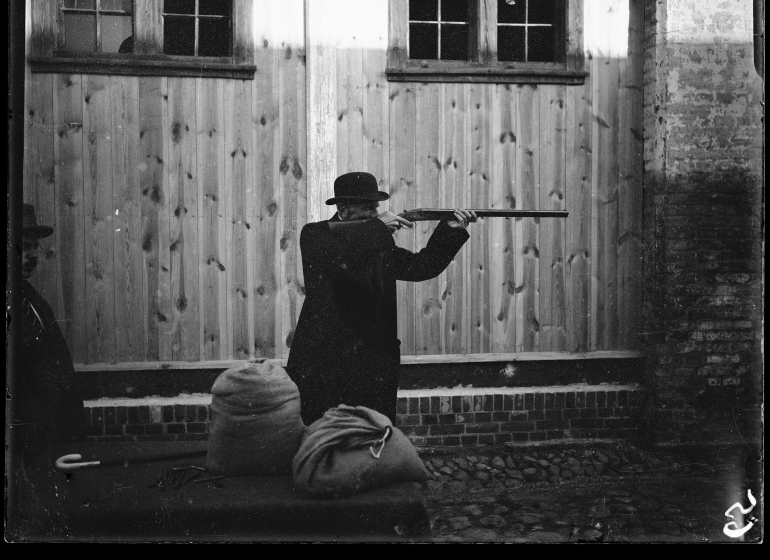

Still, the atmosphere began to thicken around young Wojciechowski. He decided to escape abroad. Going through Switzerland and France, already in 1892, he reached London. From that time on, he would stay in the city many times. To make a living, he learned the toilsome craft of typesetting, in multiple languages ; since he had known those from secondary school, he made a decent income. His top concern, however, was to bring about the downfall of the tsarist regime, along with Poland’s independence. An opportunity came with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904. Japanese intelligence officers residing in London began to supply the Combat Organisation of Polish Socialist Party operating in the Kingdom of Poland, i.e. Russian-occupied parts of former Poland. Wojciechowski would take money from the Japanese and purchase weapons (Mausers with folding stocks, and Savage revolvers) in the great city on the Thames, later to ship them to Hamburg, whence they headed to their final destinations in Warsaw, Łódź and other cities boiling with revolutionary sentiment. Revolvers are a great fit for urban warfare. They are relatively small, reliable and simple in their build. Unlike pistols, they do not require meticulous cleaning. The calibre is good, too. If the shooter aims well, the opponent has no chance. They are still used by the police in many countries. Simply put, a revolver is a beautiful weapon in the hands of true ladies and gentlemen who know how to use them.

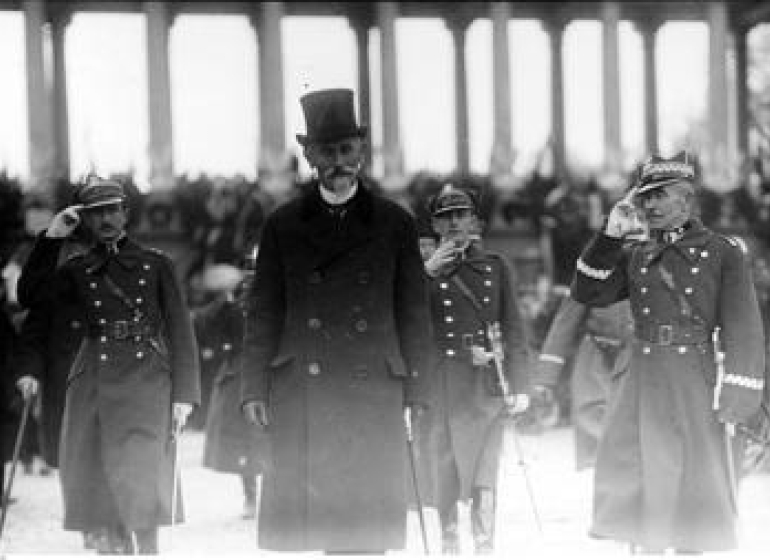

Probably the most dramatic hour came on 12 May 1926. Stanisław Wojciechowski, President of the Republic of Poland for four years, went to Poniatowski Bridge to meet his erstwhile companion from the Polish Socialist Party, with whom he had staged the revolution of 1905, except at this time they took opposing sides. Wojciechowski represented the legal government, whereas Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935) headed the mutinied troops arriving into the capital from the side of Praga. The Marshal hoped the President would step down voluntarily, but in that he was mistaken. Wojciechowski said ‘no’, and the gentlemen went their separate ways. Piłsudski allegedly had something ugly to say about that in the President’s presence.

As a result, fighting erupted in Warsaw for three days, which went down the annals of history as the ‘May Coup of 1926’. As a result, Wojciechowski was coerced to resign from the presidency. His political career was over, and his academic career began in the earnest.

As a politician, he had often shown character. As minister of internal affairs in 1919–1920, at the onset of regained independence, he attempted to force a curfew in the capital from 10.00 p.m. In doing so, he was drawing upon his Swiss and English experience. And so, he wrote: ‘That Swiss custom, also followed in England, of closing joints early and observing the night’s rest, was much to my liking; the following day everybody goes to work well-rested and well-slept, with no “Monday syndrome”. In 1919, as minister of internal affairs, I wanted to introduce it in Warsaw, but this was not to be. There are too many idlers here, who enjoy partying at night. They found protectors, who decided that any such ordinance would compound the unemployment among restaurant personnel. The welfare of dives and dancing spots came out to be more important than protecting the sanity and good rest of working citizens. We are eager to import all sorts of filth from the West, but the good habits of the West find few followers here,’ (S. Wojciechowski, Wspomnienia, orędzia, artykuły, introduction, selection of memories, speeches, addresses, accounts and articles, M. Groń-Drozdowska, M.M. Drozdowski, Wydawnictwo Bellona, Warszawa 1995). That last observation remains especially valid to this day.

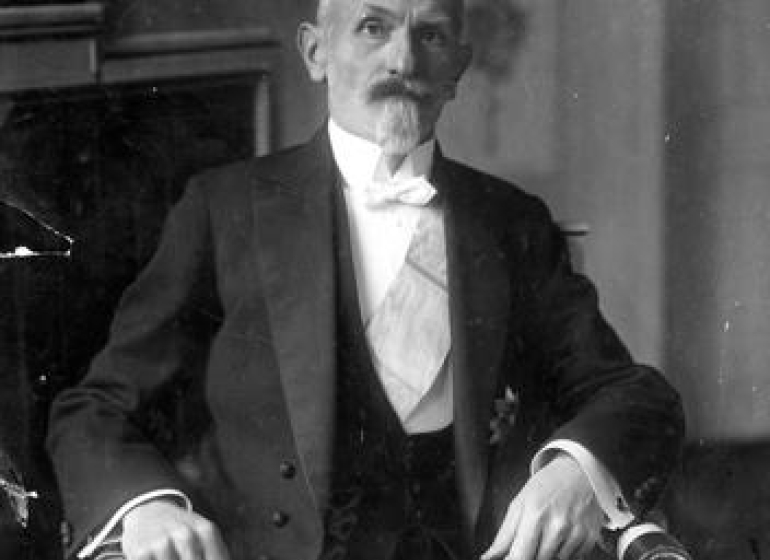

Following the assassination of reborn Poland’s first president, Gabriel Narutowicz (1865–1922), Stanisław Wojciechowski was elected to succeed him. Narutowicz’s assassin, the painter Eligiusz Niewiadomski (1869–1923), was tried, convicted and sentenced to death. The new president did not grant a pardon. The sentence was carried out.

Wojciechowski lectured at SGH in 1920–1939 with a brief interruption from 1923 to 1926 during his presidency. He specialized in the history and popularization of the co-operative movement. During the interwar period, he also taught at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences.

DR PAWEŁ TANEWSKI, senior certified curator, SGH Library.

The proposed itinerary is a short walk from the SGH campus (two tramway stops in Śródmieście direction) toward Kolonia Staszica residential district, where, at 15 Langiewicza Street, President Stanisław Wojciechowski had his luxurious mansion. Albeit the mansion in its original shape no longer exists, the nearby houses have fortunately preserved much of their original appearance. The latter was the manorial style, tapping into the tradition of old palaces and manor houses — simple, proportional houses with sloping roofs and, as a requisite, decorated with columns at the front. So, we have palaces and manor houses in the middle of the city; back then, in the twenties of the last century, these were the peripheries, though the capital was developing. The President’s neighbours were architects, captains of industry and men of science. The closest cross-street was aptly named — though quiet and romantic, it is truly presidential — Prezydencka! ‘Some names mean something even today, others are preserved only in land records, eclipsed in later years by new owners,’ wrote a famous varsavianist (J. Kasprzycki, Korzenie miasta. Warszawskie pożegnania, vol. IV. Mokotów i Ochota, Wydawnictwo VEDA, Warszawa 2004, p. 229). Well, times change. Still, we can submerge ourselves in this urban oasis of quiet and peace, trying to recall the atmosphere of the olden days, can’t we?