Financial flows between Poland and the EU in 2004-2023 and prospects for their changes

Since joining the EU, Poland has benefited from significant funds from the EU budget. But at the same time, it also contributes to this budget. In this context, the following questions must be asked: What is the size of transfers received in relation to the contributions? What are the prospects for continuing the current proportions between transfers and contributions after 2027, when the current 7-year EU budget (Multiannual Financial Framework - MFF for 2021-2027) ends? For what does Poland expend the EU funds and who benefits from them? This article attempts to answer these questions.

1. TRANSFERS FROM THE EU BUDGET TO POLAND AND THEIR STRUCTURE

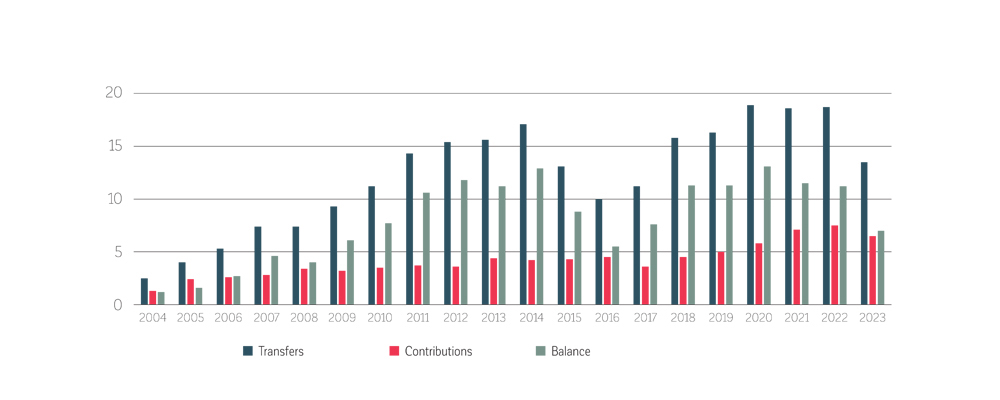

According to official data from the Ministry of Finance, from 1st May 2004 to the end of 2023, Poland received a gross amount of EUR 245.5 billion (current prices) from the EU. The amounts of the transfers varied in different years (see Chart 1), but averaged around EUR 12 billion annually, which was an equivalent of about 2-3.5% of Poland’s annual GDP (see more below). Almost two-thirds of the funds received (i.e., EUR 161 billion) were allocated to projects under the EU cohesion policy, which aims to reduce development disparities between regions and countries. Less than one-third of the transfers (EUR 76 billion) was allocated to support Polish farmers and rural areas (under the EU Common Agricultural Policy - CAP). The remaining 4% addressed other instruments, including the Connecting Europe Facility, migration funds, as well as a part of pre-accession and transitional funds which flowed into Poland after its accession to the EU.

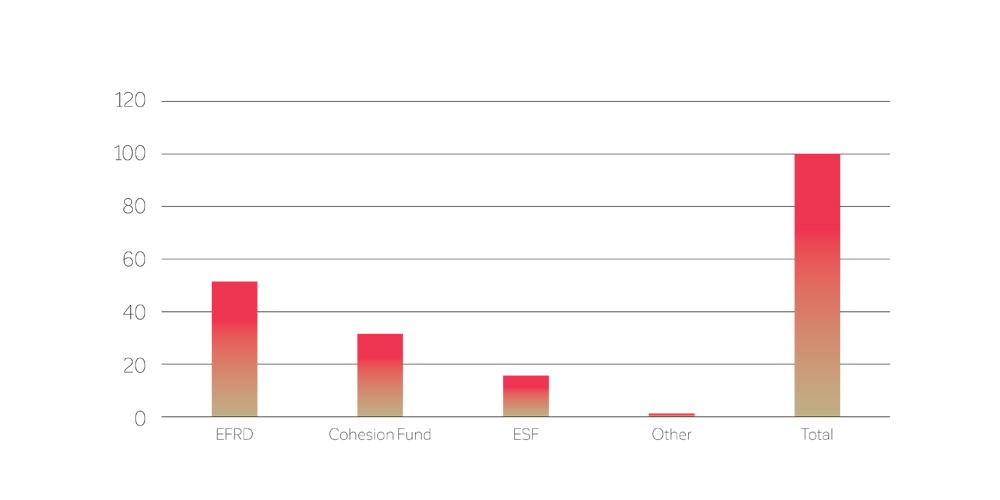

Money by cohesion policy funds1

EU cohesion policy projects were implemented for money from several EU funds: European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), Cohesion Fund, European Social Fund (ESF), and Just Transition Fund (JTF). The biggest one is the ERDF; in 2004-2023 it accounted for 51.5% of funds allocated for the EU cohesion policy in Poland (Chart 2), while in 2021-2027 it will be 62% of the total amount of EUR 64.4 billion for cohesion policy. Most of the ERDF funds went to the poorest Polish regions. The main eligibility criteria for beneficiaries were: GDP per capita in the region not exceeding 75% of the EU average GDP, based on purchasing power parity (PPP), and the unemployment rate. Since the accession, all Polish voivodships, as less developed regions, have qualified for support from ERDF. For the purposes of the cohesion policy in the 2021-2027 programming period, the Mazowieckie (Masovian) voivodship is divided into two regions: Masovian region and Warsaw Capital region. The latter is among the better-

-developed regions (average PPP-based GDP per capita was 166% of the 2021 EU average), which also benefit from the cohesion policy, although to a much lesser extent than less developed regions. The Masovian region (much more populous) is still less developed (PPP-based GDP in 2021 was 67% of the average EU income per capita). Due to this decision, both parts of the voivodship received relatively more support than if the previous solution was continued. Additionally, since 2021, two voivodships - Wielkopolskie (Greater Poland) and Dolnośląskie (Lower Silesia) - have been eligible for support for regions under transition. Their GDP per capita falls between 75% and 100% of the EU average income (in 2021, it was 83% and 86% of the EU average, respectively).2 The aim of this support is to facilitate a smoother adjustment to even lower funds in the future, when the region’s wealth exceeds 100% of the EU-27 average GDP.

CHART 1: POLAND’S SETTLEMENTS WITH THE EU IN 2004–2023, (EUR BILLION)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Ministry of Finance data, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

The second fund in terms of size, after ERDF, that Poland benefited from after the accession, was he Cohesion Fund (31% of EU cohesion policy funds allocated to Poland in 2004-2023, and slightly below 15% in 2021-2027). It is intended for less affluent countries, whose purchasing power parity-based Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is lower than 90% of the EU-average. It finances large (often cross-regional) projects in two areas of the economy: environment protection and development of trans-European networks (transport infrastructure). Private capital entities are reluctant to make such investments (due to the very long return period), so in all countries they are mainly financed from public funds. EU funds therefore reduce the burden on national budgets, which are always insufficient relative to needs.

16% of EU cohesion policy funds were allocated to Poland under the European Social Fund (ESF; 17% in the years 2021-2027; since 2021 the fund has been renamed European Social Fund Plus, ESF+ ). It is the main EU financial instrument that supports preventing and combating unemployment, as well as developing human resources (by raising and changing qualifications, among other things) and social integration in the labour market.

A new financial instrument of cohesion policy under the MFF 2021-2027 is the Just Transition Fund (JTF). It supports areas most affected by the consequences of the energy transition in pursuit of climate neutrality and prevents exacerbation of regional disparities. It is therefore a tool to mitigate the negative effects of energy transition. To achieve these goals, JTF supports investments in areas such as clean energy technologies, emission reduction, and regeneration of industrial areas. Thus, it facilitates implementation of the European Green Deal, which aims to achieve EU climate neutrality by 2050. In December 2022, the European Commission accepted five Polish operational programmes worth EUR 3.85 billion, which will benefit from financial support under the Just Transition Fund.3 They cover mining areas in Górny Śląsk (Upper Silesia), Western Małopolska (Lesser Poland), and Wielkopolska (Greater Poland), as well as in Dolny Śląsk (Lower Silesia) and Łódź.

CHART 2: EU COHESION POLICY IN POLAND IN 2004-2023 BY FUNDS, (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Ministry of Finance data, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

Since 2014, Poland has also benefited from the Connecting Europe Facility (1.5% of all transfers received by Poland, i.e. EUR 3.7 billion). These funds are managed directly by the European Commission, and are supposed to help fill missing connections in the European digital, energy, and transport infrastructure (within the trans-European transport network TEN-T). As a consequence, the financed actions are to ensure sustainable economic growth, job creation, and improved competitiveness through investments at the European level. Significant sums from this programme have been allocated to the construction of Polish sections of the Via Baltica network (an expressway from Warsaw through Lithuania and Latvia to Estonia, the main road connection between the Baltic countries, linking them through Poland to Western Europe) and Via Carpatia (a European north-south route connecting Klaipėda in Lithuania with Thessaloniki in Greece and running through Poland for a long stretch).

Sectoral structure of cohesion policy funds

According to reports from the ministry responsible for implementing structural funds, the majority of transfers (at least 60% in most Polish voivodships, and even more in some) have so far been allocated to the development of basic infrastructure (transport, energy, social, and environmental protection).4 Examples of investments with EU co-financing include construction of metro and tram route to Wilanów in Warsaw, modernisation of the Świnoujście-Szczecin waterway, construction of various motorway sections: A1, A2, A4, and the S2 expressway; construction of a waste management system for the Warsaw, Gdańsk, and Łódź agglomerations.

The remaining EU funds (excluding infrastructure and environmental protection) have been used to support the manufacturing sector (especially small and medium-sized enterprises), including businesses modernisation, and human capital development. These funds comprise also money for education and schools, as well as improvement of living and working conditions for residents (construction and renovation of public utility buildings, historic buildings, improvement of communal and health services quality).

EU funds were distributed through various programmes practically to all social groups, including entrepreneurs, farmers, local governments, non-government organisations, educational and research institutions. They have stimulated entrepreneurship and encouraged many entities to apply for financing, since part of the project could be covered by non-repayable funds. The way the funds were spent was monitored and later controlled, which has often been criticized as unnecessary bureaucracy. The experience has shown, however, that every year there are cases of unjustified expenditure, corruption, circumvention of regulations, etc. It is therefore necessary to control the spendings to ensure that the funds are used as efficiently as possible, although the scope and rate of detail of such controls are a matter of discussion.

Significance of cohesion policy funds

Evaluating the use of structural funds in Poland, economists generally agree that the money has undoubtedly improved living and working conditions of residents and overall civilization progress (thanks to the more efficient road, rail, communal infrastructure, better-equipped schools, hospitals, environment protection efforts, etc.). In recent years, the share of these funds in public investments in Poland has exceeded 50%.5 However, positive effects of these funds are less visible in terms of sustainable productivity growth, modern technologies development, and internationally competitive products based on them,6 although these proportions are gradually improving. Some actions have proven to be misguided and even started to generate costs.

On the other hand, it is also true that without the well-developed infrastructure (with motorways and expressways), the number of Polish and foreign investors who have decided to invest their money in Poland would have definitely been lower. It is also unclear, whether earlier, in the conditions of much poorer capacity to absorb EU funds, Poland would have been able to use them more efficiently for innovative projects and future-oriented scientific research.

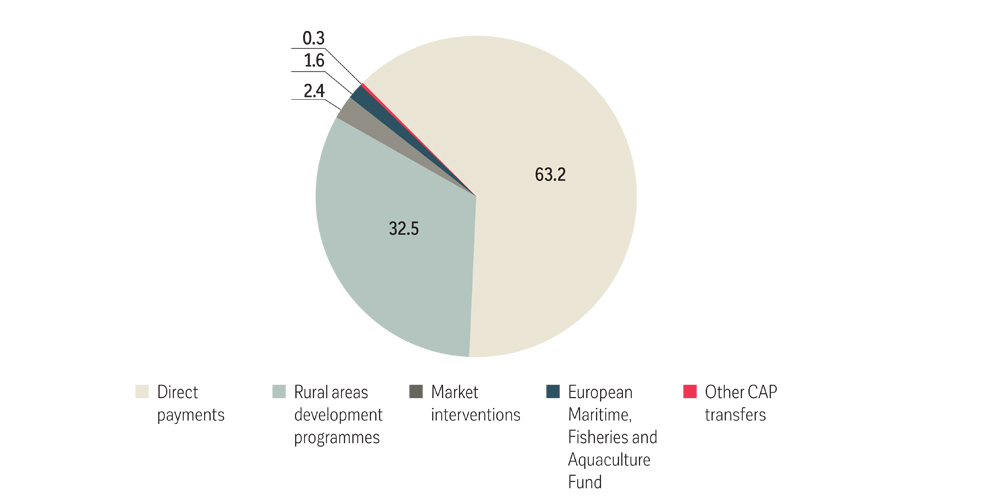

2. FUNDS UNDER THE COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY

The character and goals of the Rural Development Programme (RDP) and European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, stipulated in the CAP, were similar to the EU cohesion policy. Their aims were to modernise farms, create new jobs in rural areas, adapt products to EU requirements, and restructure maritime and fisheries sectors. Money allocated to Poland for these aims amounted to almost EUR 25 billion since the accession (32.5% of CAP funds and 10% of the entire allocation for Poland in the years 2004-2023). Other transfers under CAP (about EUR 48 billion) covered mainly direct payments made annually to farmers to support their incomes. The payments accounted for almost 63% of CAP funds (Chart 3) and 20% of total EU funds for Poland.

CHART 3: CAP FUNDS FOR POLAND IN 2004-2023, (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Ministry of Finance data, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/

transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

The direct payments have been most important for farmers, as they account for a significant portion of agricultural revenues. Although their share changed over time, they averaged about half of agricultural incomes from 2004 to 2018.7 The rest came from the sale of agricultural products. The payments’ importance is determined not only by their dominant share in the total financial transfers under CAP, but also by their widespread nature. That is because they support, to a varying degree, budgets of almost all the agricultural farms. In addition to the financial aspect, an undeniable advantage is the certainty of their receipt and stable amount. Payments are guaranteed under the CAP, and their rates are usually set for seven-year periods within successive multi-annual budgets. Such stability is of great importance in conditions of significant variability of agricultural products prices in global markets, and encourages farmers to develop agricultural production. It is also essential that farmers have the freedom to dispose of the money (they can spend it on investments as well as current consumption, not necessarily related to agricultural activities), unlike funds for rural development, which are aimed at specific objectives and are subject to filing proper applications, with no guarantee of receiving funds. The fact that Polish rural areas and agriculture had been included in CAP mechanisms, has significantly increased the revenues of rural residents. On average, no other social group has benefited from Poland’s accession to the EU as much as farmers. As a result, the income gap between rural and urban areas has decreased, although it is still significant. However, let us note that since the accession, the costs of agricultural production have also increased, partly due to adjustment of Polish indirect tax regulations (e.g., prices of fertilizers, seeds, machinery, etc.).

Direct payments, although important for farmers, have had various macroeconomic effects. On the one hand, large sums received by a small number of big farms (revenue from payments depends mainly on farm size)8 have strengthened their production potential, accelerated modernisation, and improved the competitiveness of their products. On the other hand, among approximately 1.3 million farms receiving payments, as many as 52% are small and very small ones (1-5 hectares). Some of them do not produce goods for the market, but solely for their own needs. In this case, the payments serve as social support instead of creating incentives to modernise and improve competitiveness of agriculture. They also slow down the outflow of land and labour resources from small, unprofitable farms to the market.9

Since 2023, funds for the reformed CAP have been by 10% lower (in real terms) than in the previous period. The allocation for Poland until the end of the current multi-annual budget, i.e., over five years (2023-2027), is EUR 25.1 billion, which is over 8% of the total EU CAP budget. Of this amount, EUR 17.3 billion (85% of the total) are payments, while the remaining EUR 3.1 billion (15%) are allocated to rural development.10 The proportions of CAP funds allocated for these two main types of support thus differ significantly from the previous period and assume significantly lower amounts for structural changes in the agricultural sector in the coming years.

3. NEXT GENERATION EU

During the European Council meeting in July 2020, where EU leaders agreed on the EU’s multi-annual budget for 2021-2027, an extraordinary support programme for EU countries to recover from the recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was also adopted. The programme, called “NextGenerationEU” (NGEU), amounts to a staggering EUR 390 billion11 in the form of non-repayable grants and EUR 360 billion in preferential loans. These add up to EUR 750 billion, or about 75% of the current seven-year EU budget. The funds should be spent and settled by the end of August 2026 to see their effects as soon as possible. At least 30% of all expenditures (including those under the CAP) must be allocated by Member States for climate protection, and further 20% for digitalisation. Poland’s allocation amounted to EUR 29.5 billion in grants (7.6% of total NGEU grants), ranking it fifth on the list of the largest beneficiaries of this programme. More substantial funds have been earmarked for larger countries, which were the most affected by the pandemic, such as Italy, Spain, France, and Germany.

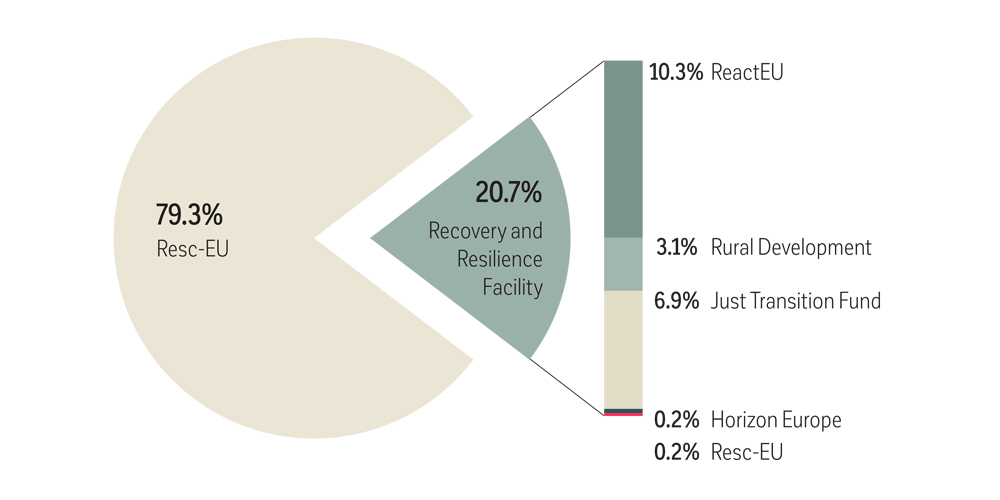

CHART 4: DISTRIBUTION OF NGEU GRANTS IN POLAND (% & EUR BILLION)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Ministry of Finance data, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

The most crucial part of the new programme is Recovery and Resilience Facility, amounting to EUR 312.5 billion in grants and slightly more in loans, of which Poland should receive EUR 23 billion (Chart 4). Like other EU member states, Poland can access this instrument after preparing a national Recovery and Resilience Plan12 (RRP) followed by its approval by EU institutions, and meeting various conditions specified in the plan.

Until the end of the previous government’s term (United Right coalition), Poland could not access the funds from the RRP13 as it failed to meet many conditions, or so-called milestones. In its evaluation of the Polish RRP, the European Commission found particularly that Poland had repeatedly and in various ways violated the principles of rule of law.14 These principles, provided for by EU treaties, were further specified in Regulation 2020/2092 (the so-called Rule of Law Conditionality Regulation). Its aim is to protect the EU budget from breaches of the rule of law principles that “directly affect or seriously risk affecting the sound financial management of the Union.”

The new government of coalition parties that won parliamentary elections on 15th October 2023, took numerous corrective measures to meet the requirements related to the RRP and prevent the loss of these funds. However, previous violations of the legal system and the division of competencies between various branches of power prove to be so significant that they require a longer time to repair the system without further legal violations. A short-term success was an application filed with the European Commission by the new government for an advance payment just two days after it took office (15 December 2023). This allowed for the first transfer of just over EUR 5 billion at the end of December 2023 (current prices). This happened despite Poland still not meeting many milestones. That is because the funds come from a new programme launched by the EU in 2023 called RePowerEU,15 which is to develop green energy as part of RRP. Advance payment provided under the programme (up to 20% of the value of the funds applied for by the Member State) was not subject to any additional requirements, which means no milestones had to be implemented. Both the European Commission and the Member States aimed to ensure that access to these funds was as simple and fast as possible, in order to reduce the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels.

On February 23, 2024, the European Commission unblocked all funds from the RRP and cohesion policy for Poland. These are huge sums to be used for socio-economic development purposes. They include approximately EUR 60 billion in the form of grants and preferential loans under the RRP and EUR 76 billion from cohesion policy. The great challenge for Poland is to spend this money wisely: in the case of RRP, there is only 2.5 years for this.

Polish contributions to the EU budget

Contributions to the EU budget are payments made by each state, calculated separately for different sources. In absolute values payments of 27 EU Member States in the current Multiannual Financial Framework amount to about EUR 150-160 billion a year.16

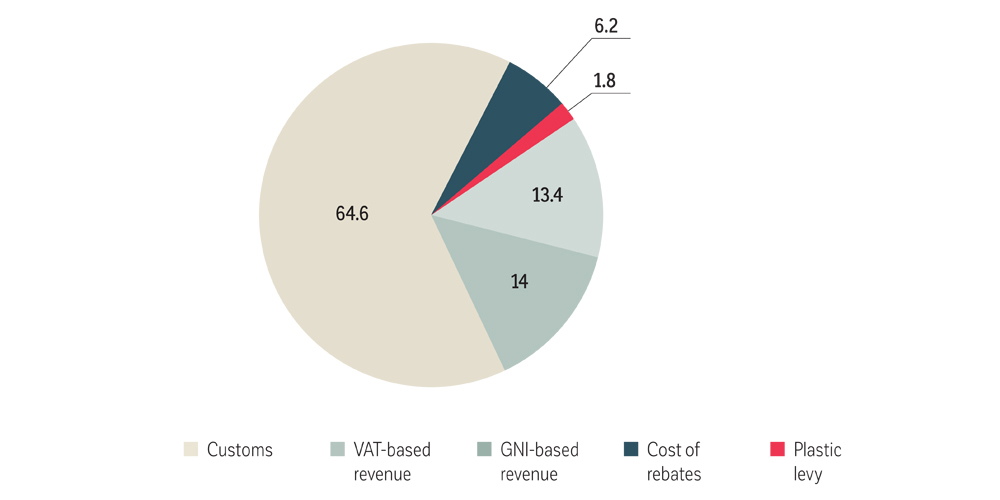

From the accession to the end of 2023, Poland contributed EUR 83.7 billion to the EU budget. This sum is equal to one-third of transfers received by Poland, which means that transfers to Poland were approximately three times higher than the contribution to the EU budget. The payments were made from several independently calculated sources. The first one is revenue from customs duties according to the Common Customs Tariff (so-called traditional own resources). In the analysed 2004-2023 period the amount accounted on average for 13.4% of the Polish contribution to the EU budget (Chart 5) The share of payments from part of VAT proceeds (0.3% of tax base), introduced later in the EU (in 1979) was similar (13.9%). The third, definitely the biggest part of the payment (64.7%)) is calculated on the basis of the share of Polish GNI in the EU GNI (this contribution component therefore reflects the wealth of EU Member States). It has been growing gradually since Poland’s accession, along with the convergence of Polish incomes with the EU average and increasing share of Polish GNI in the Union’s GNI as a whole.17

Since 2021, the three sources of financing the EU budget18 have been complemented by a new source of revenue - so-called plastic levy. Specifically, this is a payment based on the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste in each member state, and its value is EUR 80 per tonne. The amount of contribution to the EU budget therefore depends largely on the share of waste that is not recycled and is the most burdensome for those states where the rate is the highest. In practice it refers mostly to the states that joined the EU in 2004 and later, but also to some more developed EU countries, including Italy and Spain. In order to alleviate the burden of these payments, lump sum reductions of due contributions (“rebates”) were agreed during negotiations on EU budget for 2021-2027. Poland is one of the beneficiaries of such reduction, where its amount is EUR 117 million annually.19 The resultant plastic levy for 2021-2023 was EUR1.5billion, or almost 1.8% of the total Polish contribution.20

The rest of the Polish contribution (since the accession), i.e. 6.2%, was used to cover various reductions in EU budget contributions, enjoyed in the past by the biggest net contributors (UK until it left the EU, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, Denmark).21 These reductions were financed by all the other EU members, which was necessary due to the Treaty requirement for a balanced budget.

Settlement balance

After deducting contributions to the EU budget (EUR 83.7 billion), Poland received EUR 161.8 billion in net terms. In the entire analysed period Poland was the largest beneficiary of EU budgetary funds. In 2021 its share in transfers from the budget was 13.3%, although the share of a few next beneficiaries: Italy, Spain, and France, was only slightly smaller: 12% for all the transfers in each case.22 Poland’s first place reflected a respectively low level of wealth of the Polish society, compared to other EU states,23 large population (8.3% of EU-27 inhabitants in 2022) and big area of land eligible for support under CAP. In terms of the value of transfers per capita, or in relation to GDP, Poland was on further positions. In 2020 the highest net amounts of funds per capita went to Lithuania (EUR 750), Estonia (EUR 590), Latvia (EUR 530), and Hungary (EUR 485). In Poland, the amount of transfers calculated this way was EUR 330.24 Also in relation to GDP, net transfers bigger than in Poland were recorded in 2018 by Hungary and Lithuania (approx. 4% of their GDP), and Latvia, Bulgaria (3% of GDP) and some other countries. In Poland in the same year 2018 they accounted for 2.6% of GDP.25

CHART 5: POLAND’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE EU BUDGET IN 2004–2023, (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Ministry of Finance data, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

Let us note, however, that the size of transfers was lower than that of foreign drect investments (FDI) after Poland’s accession to the EU, which in 2003-2020 accounted for approximately 3.4% of GDP.26 Thus, net annual inflow of funds from the EU budget to Poland amounted to about 70% of average annual FDI.27 From the point of view of the country development, FDI have been more significant than public funds from the EU budget. This conclusion is based both on the bigger scale of financing, and the higher probability that FDI made by foreign investors have been more effective, as they have been motivated by the interest in ensuring their profitability. However, let us not forget that FDI would not have been so large, if Poland was not an EU Member State, and if the European funds did not improve its infrastructure, legal stability, and other conditions for business activity.

Evaluating the size of transfers from the EU budget from the point of view of the beneficiary, let us add that the volume of money actually invested in Poland was higher due to necessary national co-financing (except for direct payments and a few other instruments). The scope of the latter varies among specific funds and projects, between 15% of a project value (e.g. in less developed regions) and 50% (in more developed regions), while for the Cohesion Fund it is only 15%. At the same time, the projects must have been settled no later than by the end of the third year after the year of singing the respective contract (so-called n+3 rule). This rule requires the beneficiaries, i.e. both public authorities and private businesses, to perform their contracts in accordance with schedule. It also means that the effects of cohesion policy occur after some lapse of time relative to the year of contract conclusion.

4. PROSPECTS OF POLAND’S SETTLEMENTS WITH EU BUDGET

Although Poland has uninterruptedly been a net beneficiary of EU budget funds (and the biggest one in terms of the amounts received), the volume of transfers will be falling (in real terms) and soon Poland may become a net contributor, paying more than receiving from the EU budget. Several phenomena indicate such possibility:

1/ As a result of progressing convergence of revenues in relation to the EU average, Poland will gradually become less eligible for support as part of EU cohesion policy in the coming years (current EU budget rules are in force until the end of 2027). This refers both to the Cohesion Fund and to the ERDF, although in some Polish regions GDP per capita is still much lower than the EU average, and they will remain in the group of less developed regions still for a long time.

2/ There is a risk that from 2028 the EU budget for cohesion (and, possibly, for agricultural policy) will be reduced again, due to a strict stance of the wealthiest, so called “frugal” states (more bluntly referred to as “misers”), which demand downsizing of the EU budget. They justify their positions by tensions in their own national budgets.

3/ EU states face new problems the solution of which requires more and more financial resources. One of them is the inflow of immigrants and the necessity to strengthen external borders, as well as to find other solutions effectively alleviating migration pressure. New big financial needs of the entire Union are also related to the ambitious European Green Deal and the goal of climate neutrality by 2050. These challenges will continue to exert pressure to divert some of the funds from traditional areas to new tasks, such as manufacturing items contributing to the achievement of the zero-emission goal, like heat pumps, photovoltaic panels, wind turbines.

4/ Decrease in money transfers to Poland will be accompanied by a rise in contribution the EU budget, hopefully reflecting further revenue convergence.

5/ Smaller amounts transferred to Poland and other beneficiaries in the future will also be a consequence of further EU expansion. In 2024, official candidates to the EU are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine and Turkey (negotiations with the last one were suspended in 2016). These are all less wealthy countries, which undoubtedly count on support from both largest European policies: cohesion policy and CAP. Accession of each of these candidates will entail redirecting some of the funds currently flowing to the present Member States, including Poland. And despite the prospect of next EU expansion is quite distant (especially for Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova), and the probability that by that time criteria for EU funds eligibility will have been modified, the increase in the number of EU Member States must not be disregarded in the European budget analyses.

Finally, two reflections of general nature should be mentioned. First, according to a popular opinion among Poles, high net transfers from the EU budget are the biggest advantage of Poland’s joining the EU. However, according to numerous reports and studies by Polish and foreign authors, Poland benefits the most from the access to the single European market (SEM). SEM is based on four freedoms: free movement of goods, services, people, and capital. If it were not for participation in the SEM, moving goods across external Polish borders in imports and exports would cost more time and money. Some agricultural and industrial goods could not be offered for sale on foreign markets, as they would not comply with the European technical, veterinary, phytosanitary, and other requirements. The pressure of foreign competition on the quality and safety of products, and price reduction would be lower. With much lower labour emigration, unemployment in Poland would be higher, especially in the initial accession period. Transfers of money earned by Poles abroad and sent home would also be much smaller. The inflow of foreign direct investments and related economic advantages would be much lower without a free and quick access to many consumers, foreign businesses would not make their big investments in Poland, etc. All these benefits will continue even if Poland becomes a net contributor to the EU budget.

The second reflection is that the benefits and costs of economic and financial nature, however big, do not exhaust all the important effects of Poland’s accession to the EU. The accession was most of all a civilisation advancement for Poland, which included it into the area of established democracy, numerous legally guaranteed civic freedoms, area of global significance due to its potential, values, and goals. Poland has become economically and politically more secure. Especially in the face of Russian aggression on Ukraine, it is difficult to imagine the situation in Poland outside the European Union (and, obviously, NATO).

PROF. DR HAB. ELŻBIETA KAWECKA-WYRZYKOWSKA, Department of European Integration and Legal Studies, SGH Collegium of World Economy

This text uses, among other things, the following earlier works of the author: Poland’s Settlements with the European Union Budget from May 2004 till the End of 2022, and Funds Available from 2021 to 2027, in: Ambroziak, A.A. (ed.) Poland in the European Union. Report 2023, SGH Publishing House, 2023, pp. 123-141; Europejskie programy wsparcia finansowego dla Polski w okresie przedakcesyjnym oraz przepływy finansowe między Polską a unijnym budżetem po akcesji do Unii Europejskiej, in: Kluza, S. (ed.) Polska w Unii Europejskiej. Bilans korzyści, Instytut Debaty Eksperckiej i Analiz QUANT TANK, 2023.

Reference literature:

Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2020/2053 of 14 December 2020 on the system of own resources of the

European Union and repealing Decision 2014/335/EU, OL 424/1).

European Commission. (2021). Direct payments to agricultural producers, https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/direct-aid-report-2021_en.pdf

Council Conclusions of 21 July 2020 (European Council, 2020).

Definitive adoption (EU, Euratom) 2022/182 of the European Union’s general budget for the financial year 2022, OJ L 45

Główny Urząd Statystyczny, (2014) ‘Polska w Unii Europejskiej 2004-2014’.

Gorzelak, G. (2021) ‘Pieniądze z UE całego szczęścia nie dają…’, in Orłowski, W. (ed.) Gdzie naprawdę są konfitury? Najważniejsze gospodarcze korzyści członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, DOI: 10.31338/uw.9788323553489.

Kawecka-Wyrzykowska, E. (2023) ‘Poland’s Settlements with the European Union Budget from May 2004 till the End of 2022, and Funds Available from 2021 to 2027’, in: Ambroziak, A.A (ed.) Poland in the European Union. Report 2023, SGH Publishing House.

Kawecka-Wyrzykowska, E. (2023) ‘Europejskie programy wsparcia finansowego dla Polski w okresie przedakcesyjnym oraz przepływy finansowe między Polską a unijnym budżetem po akcesji do Unii Europejskiej’, in Kluza, S. (ed.): Polska w Unii Europejskiej. Bilans korzyści, Instytut Debaty Eksperckiej i Analiz QUANT TANK.

Kawecka-Wyrzykowska, E., Ambroziak, Ł. (2020) ‘Brexit: wybrane implikacje ekonomiczne dla Polski’, Gospodarka Narodowa 2021, vol. 308(4).

Kwieciński A., Zawalińska, K. (2019) ‘Rolnictwo’, in: Nasza Europa: 15 lat Polski w Unii Europejskiej, Warsaw: CASE.

Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy (2022) ‘The Impact of the Cohesion Policy 2021 of Poland and of its Regions on the Social and Economic Development of Poland and of its Regions in the years 2004-2021’, Warsaw.

Orłowski, W. (2021). ‘Źródła korzyści gospodarczych z członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej: próba szacunku” in: Orłowski, W. (ed.) Gdzie naprawdę są konfitury? Najważniejsze gospodarcze korzyści członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, DOI: 10.31338/uw.9788323553489.

Poczta, W. (2020), ‘Przemiany w rolnictwie polskim w okresie transformacji ustrojowej i akcesji Polski do UE’, Wieś i Rolnictwo, 2(187).

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10r_2gdp__custom_98…;

https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/programowanie-ps-wpr

https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/krajowy-planu-odbudowy-i-zwiekszania-o…;

Eurostat, internet databases

https://www.statista.com/statistics/253707/eu-budget-expenditures-by-pu…;

https://www.cupt.gov.pl/en/aktualnosc/various/polska-inauguruje-program…;

https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/transfery-polska-ue-unia-europejska

- Unless stated otherwise, the figures provided refer to prices from the year 2018.

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10r_2gdp__custom_98…

- One of the Fund eligibility conditions for a beneficiary is to prepare a plan for achieving climateneutrality by 2050.

- Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy. (2022). The Impact of the Cohesion Policy 2021 of Poland and of its Regions on the Social and Economic Development of Poland and of its Regions in the years 2004-2021, Warsaw, p. 7.

- https://www.cupt.gov.pl/en/aktualnosc/various/polska-inauguruje-program…

- Gorzelak, G. (2021) ‘Pieniądze z UE całego szczęścia nie dają…”, in Orłowski, W. (ed.) Gdzie naprawdę są konfitury? Najważniejsze gospodarcze korzyści członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, DOI: 10.31338/uw.9788323553489.

- Poczta, W. (2020), ‘Przemiany w rolnictwie polskim w okresie transformacji ustrojowej i akcesji Polski do UE’, Wieś i Rolnictwo, 2(187), pp. 73-74.

- 20% of the largest farms in Poland have received 69% of total payments in 2019. In many EU states the rate of payment concentration was even higher. European Commission (2021) Direct payments to agricultural producers. Available at https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/ files/2023-03/direct-aid-report-2021_en.pdf, p. 8.

- Kwieciński, A., Zawalińska K. (2019), ‘Rolnictwo’, in: Nasza Europa: 15 lat Polski w Unii Europejskiej, Warsaw: CASE.

- The amount has been complemented by EUR 4.7 billion from the national budget, thereby raising actual resources for the support of rural areas. See https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/programowanie-ps-wpr

- Unless stated otherwise, the figures provided refer to prices from the year 2018, and are therefore comparable. Council Conclusions of 21 July 2020 (European Council, 2020).

- https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/krajowy-planu-odbudowy-i-zwiekszania-odpornosci

- Still, Poland received much smaller funds from other parts of NGEU, which were not as strongly conditioned as those from RRP. These included funds for Polish rural areas and money from Just Transition Fund for “green” investments.

- Based on the Regulation the European Commission initiated a range of proceedings, accusing Poland of violation of EU law, including breach of independence of the Polish judiciary. The Court of Justice of the EU issued several judgements, where it imposed financial penalties upon Poland. Since Poland refused to pay them, European Commission offset (in several tranches) amounts due from Poland, thereby reducing the amount of financial transfers effected subject to previous MFF (according to the n+3 rule the funding could be used until the end of 2023).

- RePowerEU is the European Commission’s response to challenges ensuing from the war in Ukraine. The programme is supposed to eliminate EU’s dependence on the Russian fossil fuels, increase the use of zero-emission energy sources and strengthen European energy resilience. The value of expenditures is the same, as the EU budget must be balanced, pursuant to the Treaty.

- For the purposes of the 2022 budget, the European Commission assumed Poland’s share in the EU27 GNI at 3.78%, see: Definitive adoption (EU, Euratom) 2022/182 of the European Union’s general budget for the financial year 2022, (OJ L 45, 24.2.2022, p. 47).

- The EU budget comprises also “other revenues” (apart from “own resources”), the share of which is small (usually 1-4%) and variable. They come from, among other things, taxes paid by the EU administration, and penalties.

- Article 2(2) of Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2020/2053 of 14 December 2020 on the system of own resources of the European Union and repealing Decision 2014/335/EU (OL 424/1, 15.12.2020).

- Definitive adoption (EU, Euratom) 2022/182 of the European Union’s general budget for the financial year 2022 (OJ L 45, 24.2.2022, p. 49)

- More in: Kawecka-Wyrzykowska E., Ambroziak Ł., ‘Brexit: wybrane implikacje ekonomiczne dla Polski’, Gospodarka Narodowa, vol. 308(4), 2021.

- Own calculations based on: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253707/eu-budget-expenditures-by-pu…

- 51% of average PPP-based GDP per EU-28 resident in 2004, and 77% of average EU-27 GDP in 2021. For 2004 see Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Polska w Unii Europejskiej 2004-2014, 24.04.2014.

For 2021 see Eurostat, GDP per capita, Consumption per capita and Price Level Indices, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explainedindex.php?title=GDP_p…. - Own calculations based on: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253707/eu-budget-expenditures-by-pu… and https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TPS00001/bookmark/

table?lang=en&bookmarkId=c0aa2b16-607c-4429-abb3-a4c8d74f7d1e - https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/648183/IPOL_BRI…

- Orłowski, ditto, pp. 37 and 31.

- According to Orłowski, EU transfers were a little more than half of the average annual FDI inflows, Orłowski, ditto, pp. 37 and 31. p. 38