Among its many employees, the SGH Warsaw School of Economics had many ministers, prime ministers, senators and members of parliament. There was one President. Stanisław Wojciechowski, lecturer of what was then called the Higher School of Economics, was elected to that office by the National Assembly precisely one hundred years ago, on 20 December 1922. As the election took place during the academic semester, Wojciechowski continued his classes during his tenure.

Wojciechowski’s road to the office and to the professorial posts was neither a typical political career, nor a straightforward academic career. The man who would become President began in anti-annexation conspiratorial organisations (hence his many pseudonyms: Adam, Długi, Edmund, Latający Holender, Kazimierz Paszkiewicz, Stanisław de Lang, Wacław, Vorhoff); he then contributed to building Polish cooperative movement. He organised Poles in Russia during World War I, and immediately thereafter became the Minister of Internal Affairs in what was the key first year of Poland’s independence. But let’s start from the beginning.

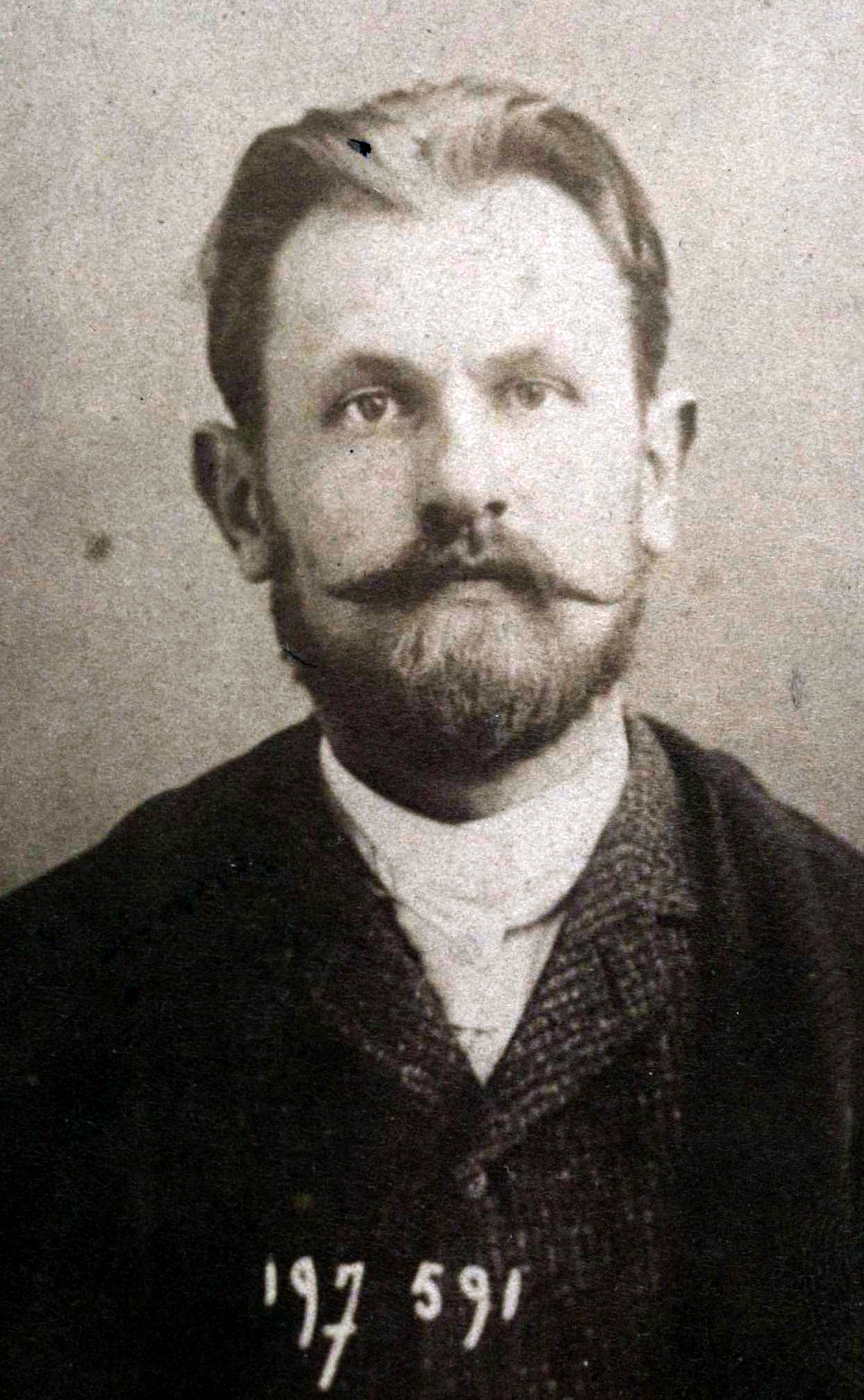

Wojciechowski was born in 1869 in Kalisz into an impoverished noble family. There, he attended the gymnasium (today, the Adam Asnyk High School) and moved to Warsaw in 1888, to study at a Russian university. Warsaw, the third largest city of the Russian Empire, was no easy place to focus on research. The generation born after the fall of the January Uprising, free from the experience of this defeat, was entering adulthood. They preferred the fight for independence instead of grassroots work. They created the first underground organisations – first united, then divided along the lines of political differences.

Like many leading politicians of what would become the Second Polish Republic, Wojciechowski, too, climbed the hierarchy of national conspiratorial organisations – from being member of the Association of the Polish Youth “Zet,” then part of its management, later serving as the President of the Student Group, and an activist in Zjednoczenie Robotnicze (United Workers’ Movement) which was headed by the renowned theoretician of the Polish cooperative movement, philosopher Edward Abramowski (more on him later). Twice arrested by the Russians, Wojciechowski emigrated to Zurich, and from there moved to Paris. He started learning his first profession – typesetting – and became friends with Maria Skłodowska. However, Saint-Petersburg laid its hands on him again. Forced to emigrate once more, he moved to England, which became his main residence for over a dozen years. This experience influenced his later views: he praised the English political system and the English sense of humour. In France, he did not find many things enjoyable, except for the cognac.

Wojciechowski’s departure from Poland did not stop his political efforts. He became one of the co-founders of the International Union of Polish Socialists and of the Polish Socialist Party. As liaison of the Union, throughout the following years, he illegally travelled to the Russian Partition to organise the workers’ movement. He travelled this road, which was key for the Polish opposition efforts, together with a slightly older friend, Józef Piłsudski. Escaping the Tsar authorities, together, they issued the underground newspaper “Robotnik,” the most significant party-related conspiratorial publication. Stefan Żeromski would later write of them as follows: “[t]here were two of them, the would-be technician and would-be physician […] If these two hadn’t made up the whole dangerous ‘party,’ what would later become the high-profile PPS [Polish Socialist Party], then not many individuals male and female would be eager to join them across this country.” Legend says it that they’d sleep under one coat, and that Wojciechowski cooked for both of them. Wojciechowski, one of the „old” companions of Piłsudski, was never a blind follower of his, however, and as it later turned out, he was capable of opposing him.

Through his friend, Wojciechowski met his wife, Maria nee Kiersnowska. She joined him in England, where she also bore their children – Edmund and Zofia. The future President still manoeuvred between his wife, who was going through difficult times, and the Russian Partition. However, he finally withdrew from conspiratorial activities, and settled for longer in an English Tolstoian colony where he took to typesetting.

Wojciechowski returned to Poland as soon as this became possible due to the amnesty which followed the 1905 Revolution. When he came to Warsaw with his family, he was no longer a member of PPS; he had quit the party after the revolutionary split and the takeover of power by the “Young Faction.” He also ceased cooperating with Piłsudski; Wojciechowski now turned to his former friend Abramowski and threw himself headlong in the motions of organisation. Wojciechowski thought independence would not be worth much without the society which has grown under the invaders’ rule being transformed. He saw the route to this transformation in the cooperative movement, to which he devoted the years preceding the outbreak of World War I. He was member of the Cooperative Society and secretary of the movement’s Information Office; he edited the “Społem” newspaper, and after prolonged efforts, he led to the establishment of and took the chief office in the Warsaw Union of Consumers’ Co-Operatives. While working on propagating the cooperative movement, Wojciechowski began writing papers on this topic. This started with Ruch spółdzielczy i rozwój jego w Anglii (“The cooperative movement and its development in England”), published in 1907. After the war, it was this activity that would lead him to higher education institutions.

For Wojciechowski, as well as all politically involved Poles, the outbreak of the war meant making a fundamental decision – which invader to side with? Unlike Piłsudski, the future President relied on Russia, seeing a greater danger to the country in Germany. Already then, he held a significant role in the Polish milieus; therefore, he became a member of the Central Citizens’ Committee of the Capital City of Warsaw and of the Polish National Committee. Following the German offensive and the evacuation of 1915, Wojciechowski found himself far away in Russia. He restarted his social and political activity. Together with Władysław Grabski, future Prime Minister and father-in-law of Zofia, Wojciechowski’s daughter, he took care of the Polish refugees from the Kingdom. After the February Revolution, he once more became involved in the invigorated Polish political environment and became head of the right-wing Polish Council of Inter-Party Union. The Bolshevik Revolution, however, saw his departure from Russia to Prussia-occupied Poland which soon regained independence.

It was then that Wojciechowski took perhaps the least known steps towards the office of the President. When Piłsudski took power and Ignacy Jan Paderewski was forming his government, the key post of the Minister of Internal Affairs was offered precisely to the old friend of the Chief of State. Wojciechowski exercised this office in the highly important first year of Polish independence. As Paderewski spent most of the year having a ball in Paris during the peace conference, the Minister of Internal Affairs served as the de facto Prime Minister. Since, at the same time, Piłsudski was often away to coordinate the fights for the state borders, Wojciechowski was the most important person in the state on more than one occasion. This was a year full of work. It started with the elections to the Legislative Sejm, the first free election in the history of the country. After that, Wojciechowski devoted himself to the task of organising local state administration, local governments and police, regulating the question of citizenship, and working on the Constitution. He used up a lot of energy for his speeches in the Sejm, which he complained about later in his memoirs.

Wojciechowski served as minister also in the subsequent Leopold Skulski cabinet, and then worked as government advisor. His efforts led, among other things, to reorganising ministries. He was unable to find himself in the Polish party system, and was unsuccessful in the elections to the 1st Senate. In line with the March Constitution, the Parliament – the Senate being part thereof – was to elect the President. Wojciechowski, who was acceptable for both the left wing and the right wing, was one of the candidates. However, he lost to Gabriel Narutowicz. Then, the right-wing circles started a hysteric, antisemitic campaign, ending in President Narutowicz being assassinated after a few days in office.

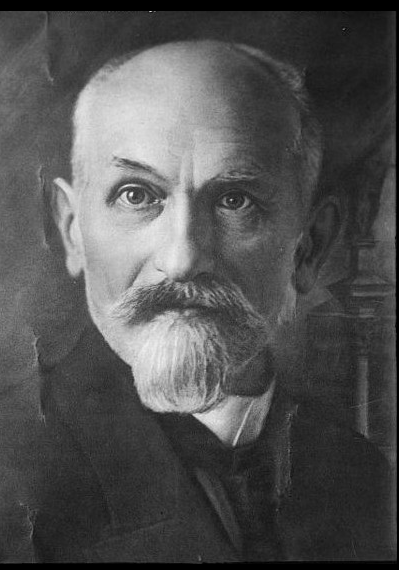

The second election saw Wojciechowski’s victory in the first round. Wojciechowski came to lead the country in extraordinarily difficult times. Poland was in ever-greater financial problems, and in 1923 the high inflation turned into hyperinflation. It was only Grabski, friend of the President, who managed to deal with it. Later on, the greatest difficulty were the growing political tensions which ultimately led to the bloody coup d’état of 1926.

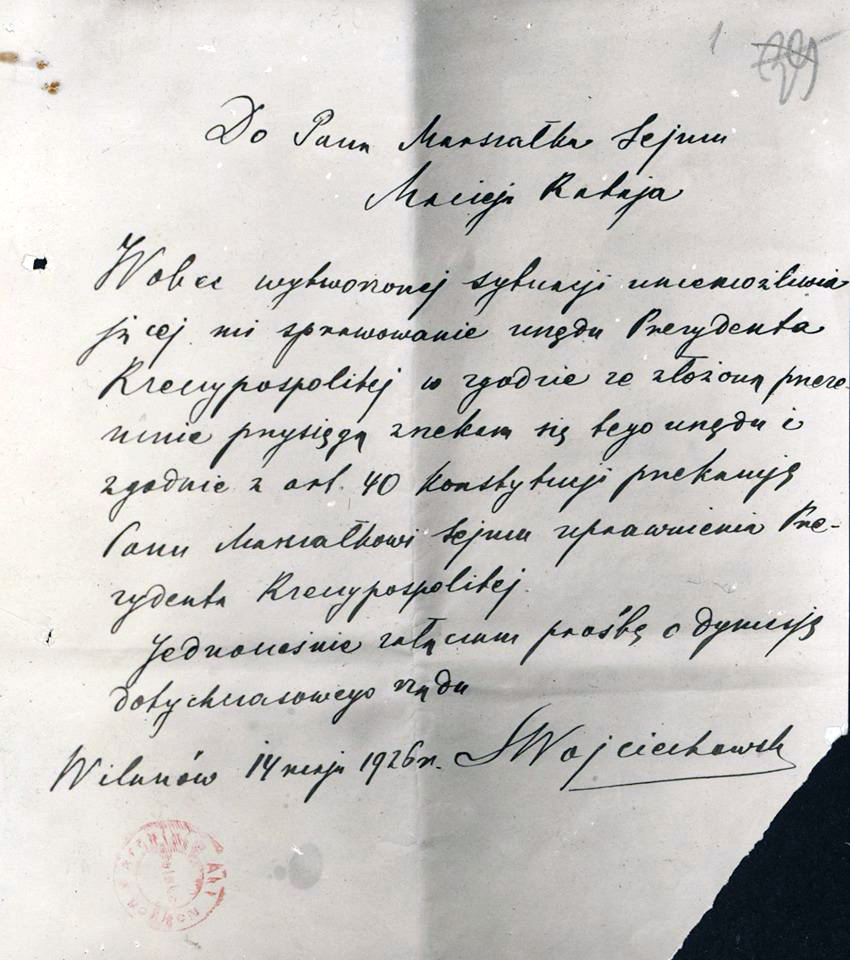

As President, Wojciechowski is mostly remembered as the one who did not give in easily to Józef Piłsudski who overtook power as a result of the coup. During the dramatic meeting with the old friend at the Poniatowski Bridge on 12 May 1926, Wojciechowski said: “Here, I represent Poland, and demand that I may pursue my claims legally.” However, when the Marshall’s army gained a clear advantage, the President laid down his arms and resigned.

Wojciechowski would find it difficult to understand today’s cult of post-coup Poland.

Committed to the rule of law, he never forgave his old friend. He rejected attempts of compromise on the part of the new authorities and withdrew from political life, devoting himself once more to the cause of the cooperative movement and to research, also at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences. He would unambiguously condemn Sanation in the very scarce public commentary he gave. For sure, this was not the independence he had been fighting for, the independence that came with persecution of the democratic opposition, manipulated elections, the Brest Trial, or the Bereza Kartuska Prison.

In the late 1930s, he started writing down his memoirs, the first volume of which was published in 1938. Wojciechowski lived through the war in Warsaw. In 1941, he lost his son Edmund who was sent by the Germans to Auschwitz. The President himself and his wife miraculously survived the uprising, during which their home burnt down in a fire together with the manuscript of the second volume of his memoirs.

After the war, Wojciechowski reluctantly returned to recreating the second volume. He settled with his family in Gołąbki near Warsaw, where he lived to see Stalin’s death, to his satisfaction. Wojciechowski himself died one month later, on 9 April 1953.

He is buried in the family tomb in the Warsaw Powązki cemetery as an anonymous citizen.

The President’s legacy needs no defending today. However, remembering him is still worth fighting for. Wojciechowski was one of the founders of the Polish independence-oriented left wing and cooperative movement, and a defender of the Polish rule of law. He was not subject to political fads, and was able to cooperate with the representatives of most political movements through many years.

We are coming close to the 100th anniversary of the day when Stanisław Wojciechowski, professor of the SGH Warsaw School of Economics in 1919-1939, took the office of President of the Republic of Poland. Wojciechowski became President on 22 December 1922.

The SGH Warsaw School of Economics, and its community which holds dear the life values of its former lecturer, has prepared a series of events to commemorate that anniversary. It will hold a seminar titled “Stanisław Wojciechowski – politician, social activist and scholar” in the Hall of the SGH Senate on 18 November, at 12:00 PM.

The seminar has been prepared by the staff of the SGH Department of Economic and Social History.

The symposium will be accompanied by an exhibition of Stanisław Wojciechowski’s publications from the collections of the SGH Library.